Saint Clair

Nuns, Bigfoot, and Fossil Ferns

Copyright 7-23-22 / 9,043 words

by Jon Kramer

Nonfiction.

Sister Elizabeth had a problem. One with little regard for the paleontological facts of life. She wanted a fossil fern, and she wanted it pronto. Never mind if it took upwards of 300 million years of time travel to get such a relic into the 20th Century. That fact was wholly irrelevant in the face of her ecclesiastical dire necessity. I found myself, thereby, on a Holy Mission.

Jon, I’m sure you have a fossil fern in your rock collection, she mentioned one Friday as school was letting out. Can you please bring one in next week so I can show it in geography class?

As any good school teacher would, Sister Elizabeth Natalia took an extracurricular interest in all her students and knew very well that I, of the two dozen pupils she presided over, was the one most likely to have such an item. Although I was not yet schooled in geology or paleontology, I was certainly an avid rock collector and constantly talked about our family trips to Scientist Cliffs in southern Maryland where I dug into the famous Miocene strata with gusto.

Technical difficulties which I will explain in a moment notwithstanding, I wasn’t about to pass up this chance to have Sister Elizabeth butter my bread with extra admiration visa-viz a special shout-out in geography class: This magnificent fossil belongs to Jon and he was gracious enough to bring it in to show us…, she’d say while patting me on the back admiringly. I’d humbly stand by, accepting the accolades: Aw, Sister, it’s nothing really… I’m always glad to help…

So, as I climbed aboard the family station wagon to head home, I assured her I could fill her request. A fossil fern would be forthcoming.

There was only one small problem: I didn’t have a fossil fern. I had fossils – plenty of them – but none in the floral department. My primary fossil site, Scientist Cliffs, is comprised strictly of marine sediments and that location represented about 99.9% of my fossil collection. The other 0.1% was a piece of dinosaur dung I’d gotten at Wall Drug. If you’re unfamiliar with Wall Drug – Google it. I don’t have time to tell you about it here. Suffice to say it’s an altogether intriguing story in itself. Maybe I’ll write about it later.

Scientist Cliffs – my first true fossil collecting site – was established in 1937 as a private enclave of summer cabins overlooking the Chesapeake Bay. George “Filippo” Gravatt and his wife Annie – both plant pathologists working for the US Department of Agriculture – originally founded the hamlet with an eye toward preservation of American Chestnut trees which, at the time, were disappearing like a magic act due to the infamous chestnut blight. They had a desperate hope that the chestnuts at Scientist Cliffs could survive the insidious conflagration due to the groves’ seeming isolation, removed as it were from other chestnut forests. Alas, the grand chestnuts wilted and died like all the rest. And, as it happened, many of the early cabins of the enclave were constructed of dead chestnut trees.

Like many pre-Civil Rights Era developments in America, the original covenants for the Scientist Cliffs development were racist and bigoted, allowing only “Gentiles of the White Race” (an actual quote from the original covenants) an opportunity to live there. In addition, you needed a college degree. The racist and antisemitic restrictions have, of course, disappeared, although you must still have a college degree or “equivalent professional experience” to buy in.

My grandfather worked at the USDA in Washington and knew Filippo who aggressively promoted his idea of an exclusive community atop the cliffs of Chesapeake Bay. Grandpa had the college degree and met the “Gentile” requirement, although he didn’t give a damn about any of that. All he cared about was getting out of the DC rat race on the weekends. Being avid outdoors enthusiasts, he and his wife Ruby took a ride down to look things over and fell in love with “The Bay”. Constructing a summer cottage get-away overlooking the Bay was just the ticket for them. And so they did, although it was some years before they could build anything because World War II intervened. Even now, eight decades on, my cousins and brother own homes at Scientist Cliffs.

Some of our earliest and fondest family memories were sculpted in those early days at the Bay. My parents enjoyed telling the story of how, one hot summer day when I was about 3, we all went down to the beach below our grandparent’s house to cool off in the ocean. While others went out in one of the small wooden rowboats, Ruby took me by the hand for a stroll along the beach. She was looking for fossil shark teeth that regularly eroded out of the cliff sediments and washed up on the sand. As we slowly ambled along the shore, we came upon a dead and decaying fish. I loved fish – not necessarily to eat, but more so just to watch them swimming in their watery universe below the surface. I found it fascinating how such creatures could just glide and dart through the water.

I stood over the smelly remains and greeted it as only a child can: Hi Fishy! Hi Fishy! Then I bent down for a closer look – Hi Fishy! and further still, until my head was nearly level with the former ichthyoid. After one last Hi Fishy!, I leaned in and kissed the carcass. At that very moment my grandmother looked over and was horrified. She hauled me into the water and washed my mouth out. I had no idea what she was doing, or why she was doing it. I still love fish, but mostly refrain from kissing dead ones on the beach.

Back to the Holy Mission: The fact I had no fern fossils was, to my paleo-ignorant adolescent mind, viewed as a minor difficulty that could easily be fixed over the weekend. We lived, after all, next to the famous Rock Creek, which, as its name suggests, has copious amounts of rock all along it. There were, no doubt, fossil ferns there – somewhere! – and I’d just go out and find some.

I spent the weekend scouring stony outcrops along the creek, my rock hammer diligently put to work, pulverizing every rock I saw. There were a LOT of rocks in that creek and it’s safe to say on that particular weekend I increased the number of them dramatically. The rocks of Rock Creek were no match for young, a nickname I acquired later. (It had nothing to do with cracking rocks – it was bestowed by an ex-con who taught me how to play billiards. You don’t know what you’re doing!, he said helpfully, when he first saw me shoot. All you’re doing is cracking balls! I’m gonna call you Kracken.) I was a one-person rock crusher. In the zeal of my fossil expedition, I cracked open hundreds – perhaps thousands – of rocks.

Alas, no fossil ferns. In fact, no fossils at all! Zero. It wasn’t until years later that I learned there was effectively no chance whatsoever of finding a fossil in Rock Creek. Quite simply, it’s the wrong type of rock. It’s highly metamorphic. If ever there were fossils trapped in the sediments that metamorphosed into the rock which eventually outcropped there, they were obliterated by deformation from the tremendous heat and pressure the strata had been subjected to on its way to becoming Wissahickon Schist, the predominant basement rock of the area.

The following week I had to sheepishly admit to Sister Elizabeth that I had no fossil fern to supply. But, as little kids so often do, on the spot I concocted an elaborate fib to cover my shortcoming: I told her I had unwittingly lent the greatest prize of my collection – a fantastic Neuropteris fossil fern from the famous Mazon Creek coal pits in Illinois, and thus a perfect specimen for her demonstration– to my friend Bart who’d apparently lost it. I explained I had only just discovered this fact when I asked him to return it that weekend so I could bring it to geography class. I acted dutifully devastated by the loss, and bemoaned the disrespect of my so-called friend Bart. It was a clever, if wholly dishonest, plebeian ruse to evoke pity from my teacher.

Sister Elizabeth was unmoved. Gee, sorry about that Jon. But these things happen, you know. I’m sure you’ll find another. Look at it this way, she enthused, it’s a good excuse to go on another fossil dig! Much to my chagrin, she did later bring a fossil fern to geography class, provided by the science teacher at the high school. It was a Pecopteris – unimpressive, with puny little leaves – nothing but a mere suggestion of a fossil fern of you asked me. But it was from Mazon Creek, perhaps the most famous fossil fern locality in the world, and it did the job. I was robbed, thereby, of my adoration dreams. At least I was upstaged by an adult and not a classmate.

When you’ve been abiding on the planet for a number of decades and, in the course of that time, taken the opportunity to reflect on your significant past events and the trails that lead to them, you will undoubtedly recognize certain twists and turns – maybe even Gordian Knots – that brought you to the particular moment in question. In one such weird twist of my life, the inability to supply my middle school teacher with a fossil fern for her geography class infected me with a fascination for paleoflora – fossil ferns in particular – that shaped a major portion of my adult life.

I first saw the incredible fossils of St Clair, Pennsylvania a year or so after my failed self-aggrandizement ploy with Sister Elizabeth. The Montgomery County Gem and Mineral Show took place each spring at the county fairgrounds. A large segment of the show consisted of museum-like showcases where club members displayed the outstanding specimens of their collections in a juried competition.

Being a young fossil fanatic, the category I was most interested in were Fossils Personally Collected in the Field. These showed an astounding array of specimens that members of the club had actually gone out and dug up themselves. There were trilobites from West Virginia, shark teeth from North Carolina, turtle shells from the Badlands, dinosaur bones from Montana, fossil fish from Wyoming, and many others. But the one that caught my eye was a snow-white frond on a coal-black shale. It was a fossil fern – Alethopteris – a common plant found in coal measures the world over. But this fossil looked positively unreal in its stark perfection.

When I first saw it, I was indignantly taken aback by what was obviously a flagrant disregard for the competition rules. In this category you were to present the fossil in its natural form. Other than cleaning the specimen and removing matrix from around it, you were not allowed to reconstruct missing parts or unnaturally enhance the appearance in any way. It was obvious this collector had painted the leaves to enhance them, a clear-cut violation of the rules.

But, wait – what have we here? This same fossil was sporting a blue ribbon! What the hell? Incredibly, it was voted the best specimen in its category by a panel of judges – from the Smithsonian, no less. Are you kidding me? An obvious fake had stolen the show? Then I read the judge’s comments: Incredible specimen! Looks unnaturally perfect. All the more fantastic because it’s real. Real? Really? Could this possibly be a real specimen, NOT painted? I could hardly believe it. I soon found it was not a hoax. It was real, natural, and wholly unenhanced. I was captivated. Never had I seen such perfect fossil preservation.

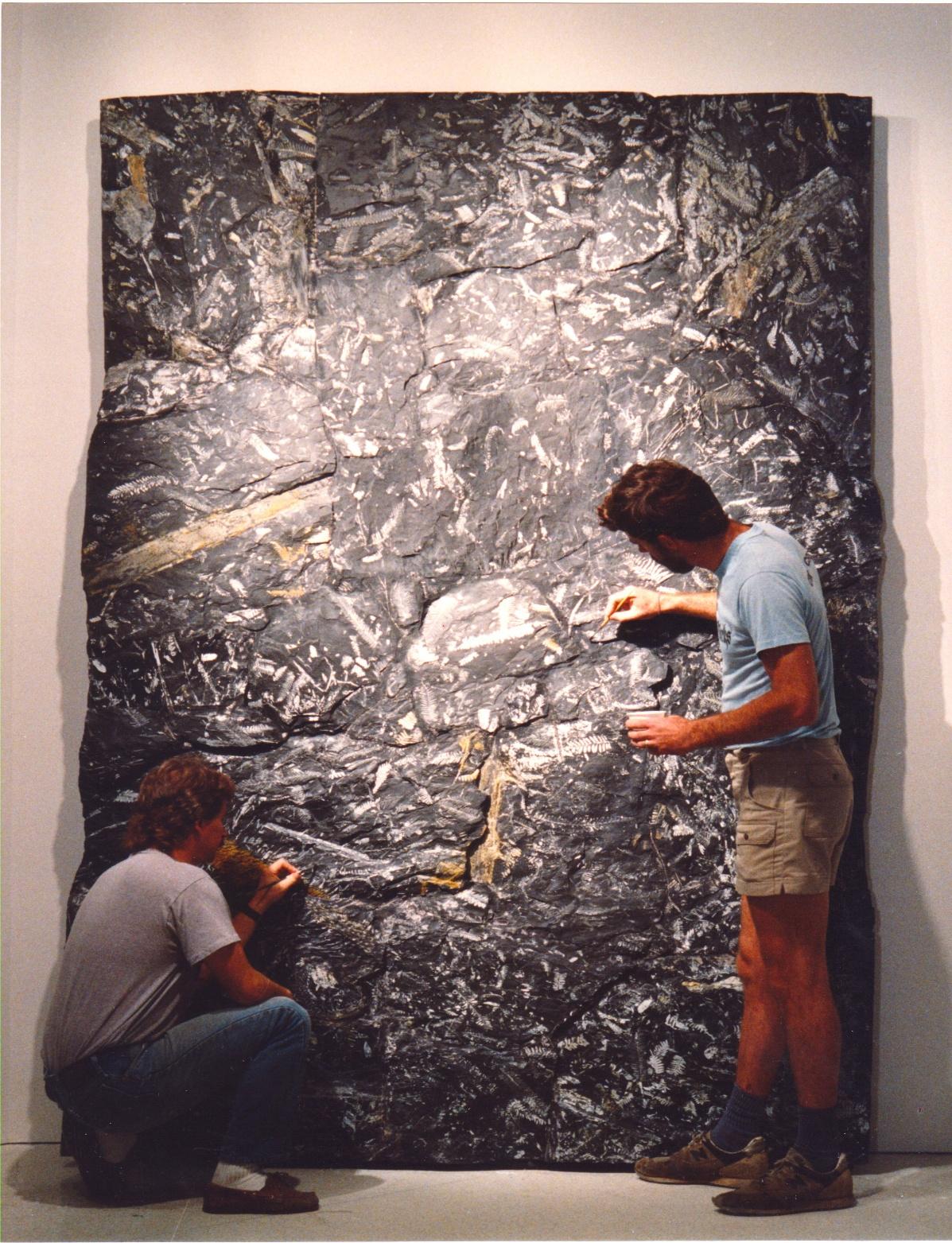

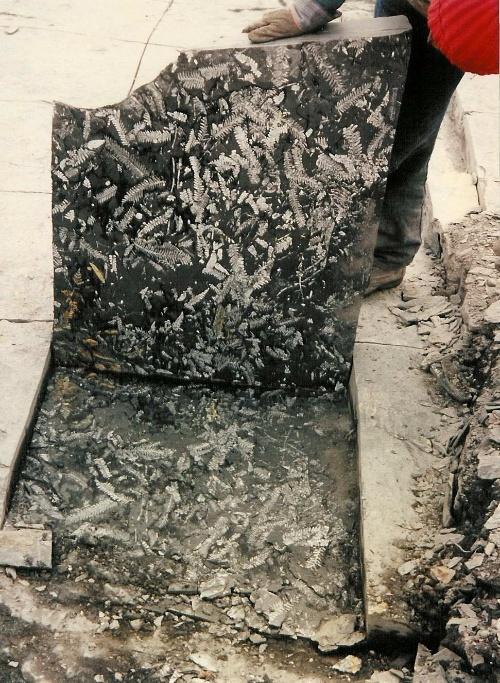

The fossil flora of St. Clair is without comparison. The snow-white leaves on jet-black shale look for all the world as if they have been painted by a skilled and precise artist. Yet it is completely natural – the result of a unique and rare form of fossilization. The original flesh of the plants were replaced by a natural white mineral – pyrophyllite. While common in coal sediments, pyrophyllite is never found in such intense and precise fossilization. In this case, however, every cell of the plant material has been replaced by the mineral. This richly-detailed preservation is known from only one tiny little site on the edge of an old open-pit anthracite mine in central Pennsylvania. And I aimed to find it.

I tracked down the owner of the award-winning specimen. Alfred was a fellow club member and he invited us over to his house to see more of these unusual fossils. I went as soon as I could get a ride. In the course of my visit, he showed me several other pieces just as astounding as the first. And, more importantly, he gave me directions to the site. Sort of.

Now Jon, he cautioned, I haven’t been there for a few years, but here’s the best I remember…

He sketched out a crude map with local landmarks: Yuengling Brewery / Reading Coal office / Tom’s lunch place. There were town names and roads, signs and landmarks. But, as I was to discover later, the details were pretty loosey-goosey. Alfred was not what you’d call a skilled cartographer. I’m guessing he didn’t earn a “Map & Compass” badge in Boy Scouts. His “map” – such as it was – turned out to NOT be directionally oriented (no north arrow), a vital detail that later nearly drove me out of my teenage mind.

Added to that was the fact the map notes, written in various places on the page with flourishes of lines and arrows, weren’t all that helpful. There was no mention of mileages and only vague directions: “Up hill behind town… Pass old buildings here… Dump piles on right, burned out car on left…. Old mattress, left side… Turn right at old dead tree…” Old dead tree? Is there only one old dead tree in the Appalachian Mountains?

The all-important detail – and reason for this treasure map – was an elongated oval in the upper right quadrant marked “coal pit” and it hosted a large X labeled “fossils”. It was outside the town of St Clair and was undoubtedly the spot where we would find some of the incredible fossil ferns. I was giddy with anticipation, exceedingly anxious to embark on a trip to coal country.

A few weeks later, in mid August, I convinced a fellow fossil hunter named Paul to join me in searching for the St Clair ferns. Paul was what you might regard today as a “conspiracy theorist”. He had all sorts of wacky ideas as to how the world worked and got much of his “news” from tabloids. To get an idea of Paul’s proclivities, Bat Boy, the completely fictious – if creative! – aberration portrayed by Weekly World News as a sometimes tenant in the White House and a serious influencer of presidents and popes – was one of Paul’s heroes. He honestly believed in this rubbish. You couldn’t argue with the guy – logic had nothing to do with it. He believed what he believed and that was that. Being a resident of DC, Paul was always on the lookout for Bat Boy around town. I attributed much of his unique idiocy to his chronic intake of cannabis and perhaps other drugs I was not aware of, thankfully.

Paul was a long-time employee of Otis Elevator. He loved his career and actually lived in an elevator shed on the top floor of a large office building in downtown DC. It was originally just an elevator shop. But when he and his wife divorced, Paul had nowhere to go. So, he brought in a cot to sleep on. Then he brought in some clothes, and dishes, and a microwave and, before you know it, he’d moved in. His boss didn’t mind: It meant that particular elevator – with a live-in repair man – was the most reliable one in town. In his spare time, Paul loved going out to collect fossils and we often teamed up since he had a four-wheel drive pickup and I had gas money.

One late summer morning, before dawn, we piled our gear into his truck and headed north on Interstate 81. The route to St Clair heads through Harrisburg, the capitol of Pennsylvania, which was, at that time, a confusing tangle of road construction. We found ourselves off-track and completely turned-around in the labyrinth. This precipitated a certain amount of anxiety which, when we finally got back on I-81 and were well out of town, was properly medicated by Paul

firing up a “fatso” as we cruised into the mountains. As I mentioned earlier, he gets his lifts from more than just elevators.

I took a few hits. I’ve never been much of a pothead, but I do love the aroma of hooch and enjoy the occasional toke. Most of the doobie, however, was consumed by the driver – probably not a good thing in retrospect. Some really potent kinds of pot carry you into a state where you are so completely zoned-out that you can hardly pay attention. I guess that’s the point of the exercise, but even so, in such a condition your sense of reasoning, as well as your reaction time, is seriously diminished. “Impaired” is an appropriate word. These are times when you should not be attempting much in the way of physical or mental exercise. Including driving. So, of course…

A few dozen miles northeast of Harrisburg there is a split where Interstate 78 branches off Interstate 81, heading to the east. It is a large, open, and gradual approach, regardless of which Interstate you prefer. The branching of the four lanes forms a perfect, gentle, wye in the roadway, parting perfectly like a wishbone. Both directions are equally as inviting to a stoned mind.

Which way do we go? asked Paul languidly as he pulled a final drag off the roach and dropped it into the ashtray. He was now in the center lane which allowed for either Interstate option. I was, at this precise time, admittedly a little zoned out and a bit slow on the uptake.

OK, lemme see… I grabbed the Rand McNally road atlas and started hunting for the Pennsylvania page. My mind was a little foggy and I was surprised to find there were multiple pages that featured Pennsylvania and its major cities. Usually there is only one page per state, maybe two. Why did Pennsylvania get six? What was so special about Pennsylvania? Why all the pages? Which page has Harrisburg on it? I was confused for a time.

Well, hurry up, Paul grumbled abruptly.

I was trying my best at “hurrying up”, but there’s only so much a stoned, half-baked mind can accomplish on spur-of-the-moment demand when confronted with so many page choices. I was muddling through the road atlas when the next thing I notice out the window is I-81 heading off to the left, I-78 heading off to the right, and our vehicle heading directly off the pavement between them. We went flying across the shoulder at 70 mph, bouncing through the ditch, slamming into the embankment and careening up the road cut. We came crashing to a stop 30 feet up the embankment amidst a flurry of rock and dirt plowed out by the front bumper.

What the hell, Paul! I yelled, exasperated, once the shock settled and I could speak again.

Good thing I have sharp reflexes, he shot back in his pot-infused stupor, otherwise we might have rolled.

This, I thought, is precisely why the older generation – and the establishment, in general – is not inclined to legalize marijuana. Miraculously the truck was intact and, just as miraculously, we managed to back down the embankment without rolling over. Luckily, we got back on the road before a state trooper showed up. Neither of us could have passed a sobriety test. Besides, the truck stank of hooch and the driver was perfectly stoned out of his mind. This being the 1970s, we’d have ended up in jail for sure.

Once back on the interstate, after a few miles, I couldn’t help but ask what compelled him to be so stupid as to drive off the highway at full speed.

Look, don’t pull this crap on me Kramer! he retorted, in stoned righteousness. I’m an elevator guy, okay? They go one of two ways – either up or down. Kind of like: Left or Right. What is so damn hard about YOU saying left or right? That’s your job! You do your job, I’ll do mine…

After Paul had finished his rant I was left to wonder: How did the roadcut-plowing incident suddenly become my fault? And further, here’s Paul with his “sharp reflexes” declaration painting himself as a hero! Maybe it was the adrenaline talking. Maybe it was his conspiracy theories and his wacky paranoia. Maybe – probably! – it was the pot. Hooch does weird stuff sometimes. Whatever, it was an ignominious start to the whole adventure. There’s an old saying in our family: The adventure doesn’t begin until something goes wrong. So, this adventure had now begun – in earnest.

We drove up into the rippled ridges of the Appalachians. These rows of mountains have been thrust up at least three times in the past couple billion years. The result is a continuous series of ridges and valleys – waves of strata that emanate from its central backbone outward to the southeast and northwest. We motored through the misty clouds, pulling off the interstate and dropping down into the tiny town of St Clair about 8:00 in the morning.

St Clair is a small hamlet tucked into a crease in the undulating mountain ridges. Like most of the region, it was established during the heydays of anthracite mining in the late 1800s. The local coal company – Reading Anthracite – has been digging the dusty diamonds here for over a hundred years. The company is not based in Reading, Pennsylvania like you’d think. The head office is in Pottsville, about 50 miles away and right next door to St Clair. Although you would never guess it today, Pottsville has a storied history which includes a National Football League (NFL) championship. Yes, you heard correctly – Pottsville has an NFL title. Or, rather, should have an NFL title.

It was the early days of American professional football. Founded in 1920, the NFL had only 14 teams when it started. By 1925 that had grown to 20 – all of which were located in the NE corner of the country. At that time almost anyone, in any town on the map, could form a team and apply to the NFL for recognition. There were three teams from Illinois, two of which were in Chicago. Even Duluth, Minnesota had a team – the Kelleys.

Perhaps the most unlikely professional football team ever was from the tiny coal town of Pottsville, Pennsylvania. With a population of only 22,000, it was by far the smallest town represented in the NFL (even Duluth had population over five times that) when they joined in 1925. Despite that fact, the Pottsville Maroons roared onto the NFL stage and took the league by storm, racking up an impressive 9-2 record going into the last game of the 1925 regular season.

The Chicago Cardinals had a similar record at 9-1-1 heading into the final season game against the Maroons. It should be noted that, at the time, the NFL did not have an official championship game like the Super Bowl. The title was simply awarded to the team with the best record for the regular season. On December 6, 1925, the Maroons clinched that record, crushing the Cardinals 21 – 7.

However, they were not awarded the championship because the NFL league bigwigs said that a demonstration game the Maroons played later – after the season had ended – violated the league rules. So, the NFL awarded the 1925 trophy to the second-best Chicago Cardinals. Most people

at the time viewed this as unfair political theater and discrimination against a newcomer from the sticks of coal country.

The entire state of Pennsylvania, and most other football fans across the country at the time, were not buying it. Even the Cardinals owner, Chris O’Brien, refused to accept the Championship title for his team. At the owners’ meeting after the end of the season, he argued that his team did not deserve it – they’d been beaten “fair and square” by the Maroons. Nevertheless, NFL brass stuck to their guns and named the Cardinals the NFL champs for 1925.

Given that the NFL wasn’t giving them the award they obviously deserved, Pottsville made their own championship trophy – a beautiful football carved out of a solid piece of anthracite coal. The town ceremoniously presented it to the team and then displayed it in the town hall. In 1964 the surviving members of the Pottsville Maroons donated it to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio where it is on display today. I must confess I don’t really follow football – I’m not into spectator sports – but will plan to visit the Hall of Fame just to see that trophy.

Some say that a curse was placed on the Cardinals as a result of the stolen title. That would easily explain the fact the Cardinals have the dubious distinction of holding the NFL record for the longest championship drought ever – having won only one title since 1925. The Cardinals also have another ignominious aspect – they’re the only team in American professional football history to score exactly 4 points in one game, the result of two safeties. They lost that game to the Racine Legion, 10–4.

I digress… back to the fossil hunt: I pulled out the map and directions we got from Alfred and read them aloud to Paul. We were supposed to go up the hill.

Oh, I get it – so it’s up the hill? he cracked facetiously. Just exactly which one of these is THE hill?…

There were any number of hills, any one of which could be what the map was suggesting. The town, after all, was in a valley – surrounded by hills, large and small, on all sides. Lucky for us it was not a very big town and we could crisscross it in a few minutes. Not knowing exactly which way to go – as there was no orientation arrow on the map provided by Alfred – we went up a lot of hills looking for something that might relate to the map and its directions.

On about our fifth trip through town, I noticed a sign on the side of a building that announced Tommy’s M & S. Below it, sort of as an afterthought, was scrawled “Lunch”.

That’s it! I shouted, Tom’s Lunch Place!

The “Tom’s Lunch Place” on the map was undoubtedly Tommy’s M & S Lunch. Had to be. It was. And that, finally, got us properly oriented on the map. A few dead-ends later, our luck turned around and we were on the right road, going up the right hill. Everything checked – the old buildings, the burned out car, the dump piles – they were all still there. Even the mattress was still in residence.

We ascended out of the valley and rose gradually up a ridge in the foggy gloom. We both were excited by the anticipation of discovering a new fossil locality. We just had to find the “old dead tree” that marked the turn. Sure enough, soon after we crested the ridgetop, we came upon a large, decaying maple right up against the road, after which was a dirt drive. We took it and proceeded through the foggy woods. In about a half-mile, we turned a corner and suddenly found ourselves in a naked moonscape: rock and shale everywhere but not a single living thing in sight.

The road descended into the edge of an old coal strip mine which ran along the side of the mountain. Although we couldn’t see very far in the fog, we got the sense this wasteland was enormous. We had arrived in the belly of the beast. Or, more appropriately, the remains of one of its many meals – a huge swath of mountain with the anthracite meat stripped from its flanks. The discarded carcass lay bare, exposing the stony bones of the mountain in its gaping wound.

Anthracite is the king of coal. It is the most densely-packed energy source of all coals – containing up to 97% pure carbon. It’s so dense it’s often carved into figurines including, as I just mentioned, at least one the size and shape of a championship football.

Anthracite burns hot, with little smoke, and produces a lower amount of tar, ash, and emissions then other coals. It was, in the 18th and 19th Centuries, an ideal source of cheap energy just waiting to be exploited. If ever there was an industrial energy apple plucked from a low-hanging branch in the Garden of Eden, coal was it. We are only just now realizing the results of our sins: huge scaring of the Earth, trammeled ecosystems, polluted water and poisoned air are the enduring legacies of coal history. Not to mention the thousands of dead coal miners killed by the dust.

Coal was, for hundreds of years, the go-to energy source. In some places it still is. The Industrial Revolution was fueled chiefly by coal. So, too, the first and second world wars. Even today, anthracite continues to play an important part in our country’s coal energy mix, although its days – like the rest of the coal industry – are definitively numbered. Thankfully. And, for the record, take it from me: there’s no such thing as “clean coal”. Any way you look at it, all coal is dirty business from start to finish.

While coal played an important part in our modernization, it no longer makes any sense to utilize as an energy source. It’s time we moved on. And we are. Those who are wailing against the arriving clean energy matrix are merely nattering nabobs of negativity and bellicose buffoons resistant to change. There have always been those types out there. I invite them to gain a little perspective of their hypocritical tilting at wind generators and solar panels by going backward in time and try living in caves for a while. Or, at the very least, try burning oil lamps for light. Change is the only constant, people: We need to get with the program or go extinct.

Looks like we found the pit, now where do we dig? Paul asked, just as eager as I to get into the rocks and dig up some fossils.

He didn’t say – just that it’s in this pit.

The “pit” we learned shortly, was not just large, it was humongous! The tiny oval on the map was, in reality, a strip mine about 20 miles long and up to a half-mile wide. Alfred neglected to mention this and had given no clue whatsoever as to where, in these endless square miles of exposed strata, we’d find the fossils.

We parked and got out. The weather had not improved. A dense overcast hung on the mountain like a dripping trench coat. The chilly fog was coursing along the ground, drifting mares-tails over the exposed black shale. It was gloomy, dripping damp, and eerily quiet.

We got our packs and gear together. Due to the near white-out conditions we had to be extra careful how we surveyed the area. If we got off-track in the fog, no telling where we’d end up. This was way before GPS – all we had were compass and maps. While the compass was an accurate Brunton Surveyors Compass, if we got lost, it would be a long way back to the truck in the fog. The map we had was seriously inaccurate to say the least.

The strip mining had bulldozed off the trees, the topsoil, and all the underlying coal along the ridgeline. This resulted in a clear line of trees that ran North-South along the barren mined-out pit. If we kept close to the trees, we could use them as a guideline to get back to our starting point and the truck.

We decided to head north. It was surreal: the overcast, the fog, and all the broken, loose rock gave the demolished landscape a post-apocalyptic feel – like something after a particularly devastating war where everything and everyone was completely destroyed. It was not a happy environment. But we ignored the depressing circumstances, eager as we were to find the spot which would yield up the famous white fossil leaves.

We plodded along in the fog, closely examining the rocks we walked on. Coal mines are excellent places to find fossil flora. After all, coal – in all its various forms – is essentially an accumulation of mashed-together organisms, mostly plants. As we scrambled along the slopping rocks, we found impressions of fossil ferns – traces of leaves in the shale. But none of them were white.

We spent four hours crabbing north along the slope and found not a single trace of white in the fossils we encountered. Periodically we stopped and dug a small pit to test the idea that maybe we were not seeing the pyrophyllite because it had been washed away by the elements. But after a foot or two of digging, we always came up empty-handed. We returned to the truck dripping wet and thoroughly discouraged, our mood as dark as the overcast.

After drying off and warming up we headed out again, determined to find “the spot”. While I was certain that Alfred had not meant to lead us astray, the enormity of this pit made the likelihood of finding the right place to dig akin to discovering the proverbial needle-in-a-haystack. Nevertheless, the siren call of undiscovered treasure is strong.

We headed south, scanning the surface for traces of the tell-tale white preservation, hoping that at some point we’d suddenly go from barren shale to rich fossil seam. It didn’t happen. The weather – and our mood – continued dank. Finally, after another few hours of scouring the broken, churned strata, we stopped at a small rubble pile to warm up a bit and consider our options. We ate cookies and drank coffee from our thermoses while sitting on discarded mounds of shale. The fog was thick and had no signs of letting up. Waves of mist periodically coated us. It was intensely quiet. We huddled there dejected.

This is bullshit!, muttered Paul, thoroughly depressed by the lost cause. Your pal Alfred has led us on a wild goose chase.

I couldn’t deny it. Alfred got us to the pit, but there was no way we were going to find the right spot without more specific information. Unfortunately, Alfred was not the one who could give it to us. He wasn’t here and even if he was, I doubt he could adequately describe where in this vast stripping moonscape we should dig. As we discovered later, he was not really paying attention to the location when he collected here. He’d been brought along by friends, a crucial fact he managed to leave out of our conversation at the time.

We sat there depressed – silently huddled on a mound of broken earth, both lost in our own thoughts. The cold mist wafted slowly over the black rubble. Most of the time we couldn’t see more than a few yards in any direction.

While contemplating our next move, I began to hear strange sounds in the distance. It was a mixture of tapping, clicking, and a sort of snorting. It was not close, but it was not too far away either. I looked at Paul – he’d heard it too. We cocked our ears toward the noise. It was unlike anything I’d heard before – an inconsistent mixture of tiny noises that repeated irregularly. Obviously, it was some kind of animal – maybe a deer or coyote off in the distance? But I’d never heard such sounds from either. Then it started to head in our direction. Whatever it was, it was gradually coming closer.

We sat still. Tap, crunch, scratch… Tap, tap, snort… There was no rhythm to it, but it kept on while getting closer. I began to feel uneasy, not knowing what it was. Was this animal rabid? It wasn’t loud, and it didn’t sound particularly threating, so we stayed put and waited. Tap, tap, scratch, snort, crunch. Whatever it was, we’d see it soon.

As the striations of fog swirled around us, we caught a glimpse of a shadowy silhouette, apparently the source of the sounds. It was some kind of large animal – a bear? It lumbered slowly in the fog, tapping and snorting and grunting. It appeared hunched over, but was definitely walking upright. Tap, tap, tap…

In the fog, it was hard to judge how big the creature was, but it certainly looked stocky. We slumped down into a depression between the piles of shale, hoping it would not see us. Both of us were on edge by this strange apparition. What the hell was it? Paul leaned into me and in a very quiet, co-conspirator kind of tone, he whispered: Bigfoot!

Bigfoot? Oh, for Christ’s sake! Here he goes again… I should not have been surprised. Paul knew damn well that all the hype about these elusive hairy humanoids encountered in hard-to-reach wilds did not impress me. Call it what you may – Bigfoot, Sasquatch, the Abominable Snowman, Yeti, Manitou, or whatever – to me it’s all just a bunch of baloney. I’m what you might call a devoted nonbeliever.

I’d heard a lot of Paul’s crazy crap over the years but now I found myself in what would undoubtedly become his tallest tale ever: a Bigfoot sighting. And, the ironic thing was, I would be his proof! Just ask Jon, he saw it too! There’s nothing like having a verifiable witness to substantiate your wacky-assed theories, especially one that most folks would consider generally sane (me) versus the source of the far-fetched flimflam (Paul).

But what the hell was this thing ambling around in the fog? It was definitely NOT a deer. And it was way bigger than a dog, or groundhog, or any number of other mid-sized animals you might encounter in these mountains. The perplexing thing was, it seemed to be walking upright. Was it an escaped zoo or domestic animal – somebody’s pet chimpanzee? From what short glimpses we had, it certainly looked ape-like. But what about the weird noises?

All this brought me reluctantly back to Paul’s goofy idea: Bigfoot? Try as I might to dispel the over-baked, anthropomorphized, late-night-movie character from my list of possibilities, I was coming up short for an alternative. Bigfoot? Could there really be such a thing?

This is incredible! Paul whispered, very excited. Gimme your camera – we need a photo…

The animal hadn’t seen as we sunk down low in the hole. We were, thankfully, downwind. It was gradually heading our way, but it didn’t notice us and appeared to just be crawling along without intention. The sounds accompanied it – Tap, tap, snort, crack, crunch… We caught quick snapshots of it as curtains of fog periodically thinned out just before another heavy drift floated in. The creature appeared to be hunch-backed. Maybe it was a bear after all. Certainly it was big enough, and a bear walking upright was not unusual. Grizzlies and brown bears routinely stand upright and walk around. Best to just keep quiet and watch from a distance.

Paul had my camera and was stealthily squirming around, itching to take a photo. He was wholly concentrating on the money shot, so much so that in the midst of setting it up he inadvertently knocked over his thermos bottle and it went banging down the slope. The animal thing suddenly stopped and turned our way. Oh shit!

Helloooo… someone there? came a voice, very un-Bigfoot like.

Hello there, I answered and waived in the direction of the voice. Paul was flummoxed.

Oh, there you are! said the aberration when he noticed us through a parting in the fog.

He came over and in short order we found that Bigfoot was actually an old retired coal miner named Joe O’Malley.

Old Joe, they calls me. One of the O’Malley’s of Pottsville! he declared.

He lived not far away and was out for his daily walk. Actually, it was more of a hobble, as he relied heavily on the walking stick he carried. That, as it turned out, was the source of the tapping sounds. The scraping and crunching came from his old steel-toed boots grinding the shale as he hobbled along. He wore an ancient black oilskin rain slicker and battered clothes to match. If you put a hard hat on him, and placed a pick-axe in his hands, he’d look exactly like one of those kitschy knick-knacks you see made out of coal powder and resin that are sold in the tourist traps of every coal town on the planet. I invited him to sit and have some coffee with us.

Don’t mind if I do, he enthused. The fog is a bit bracing…

I’m bettin you’re not just out for a stroll in this weather, Joe said with a hint of Irish accent as we sat shivering in the mist, sharing our coffee. I’ll be guessin you’re looking for them fossils…

I confirmed his assumption: After spending the whole day wandering in the fog and marching umpteen miles across the baren, black, shaley slopes, we had not a single decent fossil to show for it. We were nothing if not frustrated by the experience of hunting the elusive prey. We knew the fossils were here -somewhere! – but as it was now late afternoon, we despaired of finding any before the light faded and we had to head home.

Well, I’d guess a fellow just needs to be diggin in the right place… he said, Quixotically, as if to torture us.

We chatted awhile about Joe’s history in the coal mines. His grandfather had come over from Ireland during the Potato Famine and started in the mines right away. His dad grew up in the mines and Joe followed. Wasn’t much else a boy could do hereabouts… By the time he was ready to retire he had worked just about every job you can in a coal mine. After 40 years underground and above, he called it quits. He even hauled coal out of the very pit we were sitting in.

On my last payroll, I drove truck for Reading. We hauled Mammoth Vein coal from this very strippin. Long days, I can tell ya. The road came in over yonder and made a bend so sharp we called it Dead Man’s Curve. Some guys actually did go over before they fixed it, tho I’m not sure if any of them ended up dead….

It got even more titillating: Yep, I was here when Danny Lomax – Max we called him – pulled out the first pieces of them white ferns you’z lookin fer. Yes sir, I was. “Max, I sez, did your kids paint them things?” But then he breaks one open right before mine own eyes, and – lo and behold! – leaves as white as the virgin snow… Curious it was, we found em only in one little area. But I got me a-plenty. Gave em all away, I did, to grandkids and such.

So where, exactly, was that Joe? I asked straight-out.

He ignored the question and started in about how his great uncle Thomas had thrown in with the guys who started the brewery over in Pottsville – Yuengling, it was, that very one! – and made a killing hauling beer when Prohibition was lifted in the early 30s. And how Thomas’ daughter Emily – his mom – had made cookies that became so famous the governor himself ordered them from Harrisburg. And how his Cousin Willy….blah, blah, blah…

All that’s great, I thought to myself, but where do we dig for chrissakes!? I wanted to scream!

Joe obviously relished telling the story of his life as we sat there waiting for the vital

words about the exact location we should be digging in. He knew we were anxious, almost desperate to find the fossils. But as he rambled on about ancestors and relatives and “the kids these days”…, it seemed he would never get to the point. When he veered into local politics and religion, I knew it was hopeless. Nothing’s worse than politely sitting through a long sermon from someone you don’t know who’s lamenting the state of the world today and proselytizing about how people should live their lives. God help us!

It eventually occurred to me that Joe enjoyed the fact we didn’t know where to dig. We were, after all, strangers from the Big City – DC, no less – The armpit of the country, he called it. As inanimate and valueless as it was, we wanted something he had – something he had no intention of giving up to a couple of outsiders. Never mind it was effectively a worthless possession and would cost him nothing to give it. The fact was, as much as we wanted it, there was no way we were going to find the right spot to dig on our own. Joe knew this and loved keeping us in rapt attention. There is power in knowledge unforthcoming. It sucked.

But what could we do? We obviously were not going to find any fossils that day so we might as well sit here and listen to an old-time miner tell us about his life. When I finally let go of the idea of digging fossils, I found Joe’s stories interesting and began a dialog with him. Especially when he touched on local coal mine disasters. Pretty soon, between the two of us the Coal Mine Tragedy Hour got cranked up, much to Paul’s chagrin. Paul excused himself, saying he needed to take a pee. He took the opportunity to also fire up a joint and sat off in the distance – downwind – getting stoned. If you can’t dig fossils, may as well dig some fine Mexican weed.

I crowbarred my way into the conversation by mentioning to Joe that my paternal ancestors worked and died in the underground anthracite mines in this very district – just up the road in Wilkes Barre. Our family history has plenty of coal mining stories from this region.

You don’t say!, he exclaimed, obviously excited. That’s up by Plymouth, where the Avondale Mine was. I had kin meet their maker in that one… He dove into the story – as told by his grandad – of the massive fire at the Avondale Colliery in 1869. It started when the wooden lining of the mine shaft caught fire and ignited the coal breaker built directly overhead. The conflagration killed 110 workers. It was the greatest mine disaster in America up to that point. Joe had family that died there.

I then related the story of my great grandfather – George Kramer – who, in 1907, was trapped in a tunnel of the Wanamie Number 18 – which was right next door to the Avondale Mine – with barely enough oxygen to keep him alive, if you want to call it that. When he was finally pulled out, his brain was so scrambled his entire memory had been wiped completely clean. He had no clue who he was, where he was, how to speak, or even how to drink or eat. He’d become an infant again and had to be retaught everything.

I remember hearing about that feller! Joe exclaimed, to my surprise. Daddy told me a

‘bout him.

Do you remember the Knox? I asked, knowing full well that anyone who grew up in this region would undoubtedly know that story.

Darn right, I do! he hollered. Those bastards told the workers to dig right under the river!

The Knox Mine Disaster is among the most famous in the long, long list of American coal mine tragedies. It’s not because of the death toll so much as the completely avoidable calamity of it. In January 1959 workers in the Knox were ordered to dig into a coal seam that ran under the Susquehanna River. This was patently illegal, made so for obvious reasons. However, the mine owners and managers – greedy, ignorant of geology, and with no concern for anyone’s safety – ordered the crews to dig it out anyway. The problem here was compounded by the fact the vein sloped upward toward the river.

As you can imagine, eventually the rock layer above became too thin and the roof collapsed. With it came the entire Susquehanna. The river poured in, flooding into the many interconnected mine tunnels and galleries on both sides of the river. Twelve miners were killed. Plugging the hole in the riverbed took over three days and the creation of artificial mid-river islands over the site. Look it up on YouTube – there’s video of them running train cars off the track into the huge whirlpool to plug it.

From that point, Joe and I carried on like long lost relatives – running down mine history and local folklore. He took to calling me Johnny. I didn’t mind; the way he said it was endearing. We rambled on for well over an hour. Eventually gray gloom started to settle in and we both noticed it was getting late – time to go. The damp fog still had not let up.

It wasn’t an altogether fruitless adventure. In my thinking, meeting characters like Joe along the way is as rewarding as finding fossils. Or not finding fossils, as the case may be. I started putting stuff into my pack and yelled over to arouse Paul who was, by now, a complete Zombie prone on the ground, covered like a cadaver by his rain parka. Joe rose creaking onto his feet and leaned on the walking stick, steadying himself.

Too bad you ain’t found what ya came for, Joe said. That was a strange comment. I couldn’t tell what he meant by it: Did he just not remember where the fossils were, or was he determined not to tell us, for whatever reason? Either way, at this point, it wasn’t all that important now that we were leaving.

Oh, no worries, I said. Maybe we’ll have better luck – and weather! – next time.

He turned to go, but stopped momentarily: Say Johnny – ya wanna know somethin funny? he said, as he stood there with a smirk on his face. If you dig right exactly where you’re standing, you’ll find them.

You’re kidding! I yelled in protest. He laughed heartily and tap, tap, tapped his way off into the fog.

We saw Old Joe several more times over the years. He usually came by in the evenings after we had stopped digging for the day, always happy to sit and shoot the breeze. We shared stories and Yuengling Lager. He never tired of telling the crew about the first time we met – Here they waz, sittin right on top of the fossils and didn’t even know it!…

The last time I saw Joe was about six years later. He wasn’t looking good. He groused a little about how his body was failing him and his walks were tiring him out. When he left and we shook hands, his was weak and foreboding, imparting in me a moment of fear – one that I quickly overcame in the ways we do when we kid ourselves that it’s not what we think. But it was.

Ya know, Johnny, he said, before he left for the last time, your kinfolk and mine are part of these hills. I suppose we’ll all be one day… In his case, that one day came not long after. A few months later when we came up to dig again, our equipment operator told me that Old Joe had joined his relatives. He was buried over in Pottsville.

For over thirty years we excavated fossil ferns in the very spot where we first sat with Old Joe O’Malley, sharing coffee and history on that gloomy August day when a tapping sound came to us in the fog.

But it wasn’t Bigfoot!

AFTER WORDS

Not many years after disappointing Sister Elizabeth, I actually did find a fossil fern, the story of which is related above. Within a few years I had excavated many thousands of them. And, in the course of three decades with my Potomac Museum Group compatriots, I oversaw excavation of about 250 tons of fossil ferns. That’s 500,000 pounds – enough to fill 20 semi tractor-trailer trucks. The resulting specimens were sent to museums, schools, nature centers, scout groups, and educators the world over. And, I should add, even to nuns teaching middle school geography.

Although I doubt there is a category for it in the Guinness Book of World Records – an understandable, if lamentable, shortcoming on their part – I’m fairly certain that I would hold the official title for the “Most fossil ferns ever excavated by a single person”. Wherever Sister Elizabeth is, I hope someone will tell her I am now capable – and willing! – to fill her order, although, by now, she probably has an address in Saint Peter’s book, which would require delivery to Heaven (I assume she went up instead of down, although I can’t be sure). I will hastily add that I am not prepared to make such a delivery myself anytime soon but if the Post Office would consider it, I will happily send it via Special Delivery.